Tom Otterness, Feats of Strength, 1999

Tom Otterness, 1999.

Bronze. 15" h.

Photo credit: David Scherrer

Western Washington University in partnership with one-half of one percent for art law, Art in Public Places Program, Washington State Arts Commission.

Description

Walk around the sculptures with Google Street View

Tom Otterness and Beyer share common ground not only in their skills in engaging the public but also in their interest in types of narration. Since Otterness' Feats of Strength (1999) has come to the University, one cannot help but look again at or revise formerly held opinions about Beyer's troll-like ''old man'' and Osheroff's and Melim's Disney-like animals at the Ridgeway Complex. Otterness enlarges his character sketches beyond Beyer's native folklore to create a narrative cycle in Haskell Plaza where global references reverberate. While Otterness works in bronze on the same small scale as Osheroff's and Melim's ceramic figures,-beaver, fawn, or owl- he goes beyond these artists/craftsmen to change the role of decorative scale. Rather than using the typical monumental scale of public art, he miniaturizes his figures, but he still gives them the same seriousness of most allegories found in large stone monuments in public squares. He embraces the fantasy scale of Disney and Looney Tune Cartoons, but places the viewer not in front of a distant cinema screen but rather seats them directly at tables or in tablescapes.

Full text

On campus, Otterness watched the constant pedestrian traffic as well as the leisure activities of Haskell Plaza while sitting at times on one of the sandstone rocks and at other times on the concrete ledge of the inner circle. At that eye level, he could see the plaza or landscape more like the surface of a table before him where, like a child, he could move his characters around. In his work for Western, Feats of Strength, Otterness placed one figure on the ledge where he himself had sat; the moon-eyed figure holds a rock as if it were a moneybag. In some cases the ledge acts as a frame or is contiguous with the grassy mounds where students sun themselves; here, Otterness placed one of his laid-back figures. At other places the sandstone boulders on the mounds reach over the concrete ledges; there, Otterness tucked some figures working under the rocks. Within arm's reach of the ledge where the viewer sits, he also placed a group of figures carrying one of the boulders out into the middle. Also separated from the other sand stone boulders, the landscape architects had placed a granite rock at the request of the Geology Department. Finally, Otterness built a female Atlas-type holding a boulder on top of one of the largest rocks where students rest their backs while reading, thereby confronting the gender issues often implied in the work of Morris, Pepper, or Serra.

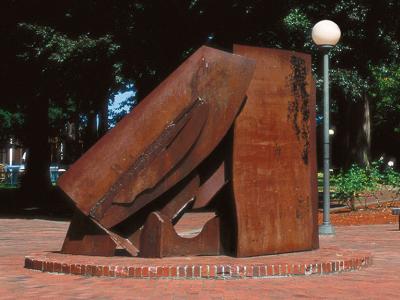

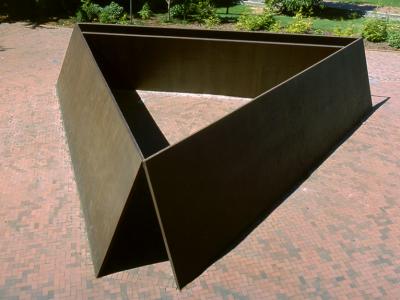

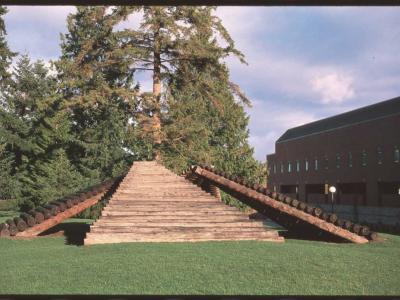

Since the eighties, Otterness has put his figures in complex scenarios of human behavior ranging from themes of birth and death, time, labor and money, class struggles, to engaging in battles of good and evil, including Utopian nature and postindustrial destruction. At Western Otterness found the landscaped plaza by Campbell & Campbell. They had excavated and utilized the sandstone boulders that had been submerged in the ridge that now holds the Chemistry and Biology buildings to create a plaza replicating on a miniature scale the San Juan Islands beyond the hillside University. Otterness' figures intervene to perform feats around these once submerged rocks on the plaza. When he was executing his ''colossal two feet turned upside down as bench'' for the Krannert Museum in 1994, Otterness had remarked that ''the idea of a submerged monument is a metaphor for the mysterious or un known part of society-maybe like a past society or a future society. Using the Museum of Natural History in New York as his college, Otterness had become fascinated with archaeology and its buried monuments, fragments of memory. Haskell Plaza is surrounded by the academic buildings dedicated to the sciences, technology, and business. On a whimsical level, Otterness' seven small-scale bronze figures lifting and pushing rocks and/or sitting and lying on a ledge seem to be the faculty and students simply working and relaxing in this University setting. But Otterness also found in the plaza two existing sculptures: Beverly Pepper's Normanno Wedge, a monument to tools, and Lloyd Hamrol's Log Ramps, a structure referring to natural resources and indigenous peoples. Therefore, on a more serious level his vignette reinforces the idea of natural and cultural forces at work in the region today. The small scale of his vignettes calls particular attention to the overwhelming forces of nature-in this case, various kinds of rocks:-as well as the ongoing feats and the hopeful intelligence of man. When Western's sculptures are placed in new con texts, entirely new narratives can be read. In Haskell Plaza, Otterness' sculpture exists together with Pepper's wedge-shaped sculpture and Hamrol's ramps. Turning all the way around, the viewer can see the past in geo logic history, the primitive tool, and the primary log structure. He can see the present referenced by the inhabitation of the region and islands, both the real and the miniature version; and he can see the future in the intertwining of natural and man-made resources on this University campus.

© Sarah Clark-Langager