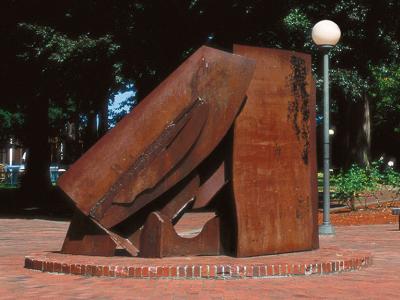

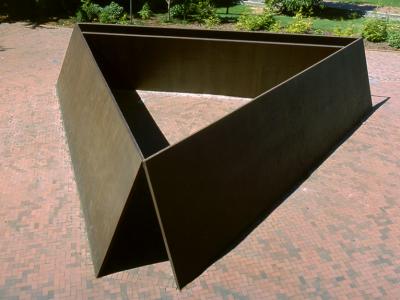

Beverly Pepper, Normanno Wedge (1980) and Normanno Column (1979-80)

Beverly Pepper, 1980.

Cast iron. Column: 7' 3" h. Wedge: 102' x 11.3" x 11'3"

Photo credit: Jesse Sturgis

Normanno Wedge: Western Washington University in partnership with one-half of one percent for art law, Art in Public Places Program, Washington State Arts Commission. / Normanno Column: Gift of Virginia and Bagley Wright, 2005, in honor of Karen W. Morse, President, and Sarah Clark-Langager, Curator. Installation funded by Virginia and Bagley Wright and President Karen W. Morse's designation from the Amendt Presidential Endowment.

Description

Walk around the Normanno Wedge with Google Street View

In her two totem-like markers in Haskell Plaza, Beverly Pepper combines the image of tools with the idea of civic monuments. They are the products of tools, literally but also metaphorically as the spiritual products of the tool-using culture that the commemorate.

Just as Abakanowicz sensed the enchanted quality of the cold forests of Poland or the primitive nature of the tropical rain forests of Papua New Guinea, Pepper was transfixed by the thick growth and gnarled trees interpenetrating the Buddhist carved reliefs that covered the temples at Angkor Wat in Cambodia. Caro, too, remembered similar encrusted temples in India. While both Abakanowicz and Pepper have created a sense of a total environment in a singular object and have made a large environment with one type of object, Pepper's interest was the sense of transition one finds in any culture's tools.

Full text

Her experimentation with materials, whether wood, earth, metals, or their combination, might belie her real intent to bring the past into the present or to have ''the past to participate in [the] presentness'' of her sculpture. Although she began her career as a painter, Pepper's experience at Angkor Wat turned her to sculpture. Yet, when she changed from two to three dimensions, Pepper worked from a tradition of sculpture as did di Suvero, rather than reacting against the illusionism of painting in a literalist manner as did the minimalist Judd. Both she and di Suvero wanted to be directly involved in their art processes rather than using fabrication or mechanically reproductive means to enlarge sculpture from maquettes as had Noguchi. She was one of the first to use Cor-ten as she liked its intrinsic color, a rusted patina from the exposure to the sun. But it was the (earthen) iron's endurance through time and its sense of prehistory that gave her the greatest inspiration. First discovered through meteorites, the Sumerians had described it as ''celestial metal'' and the Hittites knew it as ''the black iron of the sky''; then, found in the veins of the earth, smelted iron was worshipped as a gift from the deep earth god of fire.

Pepper acknowledges the immediacy of a tool as an extension of herself, just as the crane is for di Suvero. Then, she takes the tools of technology as a point of departure, either reinventing shapes or repressing the original use of the found object. For example, when she was in Iowa at Herbert Hoover's birthplace, she was impressed by an axe in an old barn. Later, two axes emerged in a vertical sculpture as part of her Urban Altars series. Normanno Wedge (1980) at Western is one from this series.

Sensing early industry's tools, such as axes, chisels, drills, and files, are already parallel with those of the Iron Age of the Hittites, Pepper gave vertical form and the look of ancient, sacred iron to her new markers. As in Normanna Wedge, the uneven quality of the iron, the worn edges (wood cast in iron), and the darkening patina suggest that time marches on.

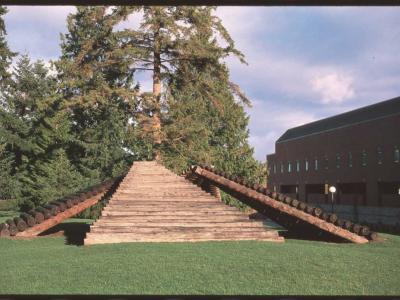

Similar to Westerlund Roosen, Pepper used the irregular form of the wedge, not the rigid rectangles, perfect circles, or sharp diagonals of the minimalists. Pepper's choice also makes one believe that the shape has been dug from ruins rather than fabricated in modern factories. In siting Normanno Wedge at Western, she was concerned that the work did not relate perpendicularly to the buildings or any major pedestrian path. At the time, the future Haskell Plaza was only a grassy area, so that a clear sense of procession occurred from the steps between Environmental Sciences and the new Parks Hall (College of Business) to the major path in front of and along the facades of Environmental Studies and Arntzen Hall. In turning the thin edge of the wedge on a southwest/northeast axis she negated this sense of the processional, but she still retained the sense of columns and obelisks as guides through a city just as skyscrapers today are visual markers. Therefore, when the viewer comes up the steps from the south, Normanna Wedge marks the place (at first a grassy area, now an institutional plaza); on a mound, it thrusts itself against the sky. Just as an axe can signify violence, a wedge or plow implies the intertwining cycles of man and nature. But in Normanna Wedge, civilization's tool slides or slices into a circle, an abstract symbol of the void or sky. However, when viewed from the front door of Parks Hall, the wedge shape is only a raised flat plane. Using the format of the free-standing altarpieces of medieval cities, Pepper created an abstract frame, picture plane, or altarpiece for an urban or modern space. Just as the four years of a student's life is short yet filled with personal history and new revelations, Pepper's new monument is not limited to any specific event. By creating a plane on which to rest one's eyes and a mark against the sky, she points to the idea of memory itself and how it shapes the future. Totally abstract, the sculpture alludes to the sense of transition in all of society's tools - from iron wedge to computer--and to the power of memory to effect and color change.

© Sarah Clark-Langager