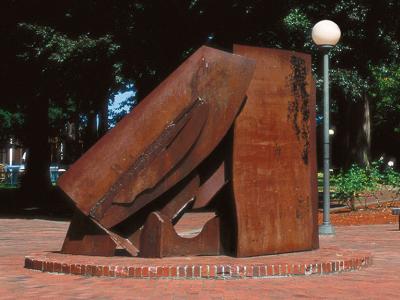

While Noguchi's sculpture can be described as a tilted cube with cutouts on three sides, its special qualities are weightlessness and its continuing sense of space. Rising on brick piers, the sculpture invites the viewer into its interior. Inside, the viewer can measure himself against the scale of the cube and sense the uplifting of the sculpture as he looks up and out towards the moving sky. Since in Japan the circular disk represents the sun and is a symbol of creation, and since the viewer is part of the sculpture, Noguchi provides here a subtle union of two creative forces - man and nature.

With poise and grace, Skyviewing Sculpture (1969) balances its cubic shape on three points above the pavement of Red Square. Noguchi, the creator of this sculpture that seems at times to float over the square, and Ibsen Nelsen, the architect who commissioned the work for this University space, had in common their admiration for an older model, the Piazza di San Marco in Venice. After a visit to Italy in 1949, Noguchi actually described this older Italian square as a ''gigantic drawing room where the outside permeates the inside.''

Full text

At Western, Red Square has long been the center for students who enter and exit the buildings on the perimeter: going to childhood to adult education classes in Miller Hall; entering the Humanities building; back and forth to Bond Hall for math; checking experiments in sciences at Haggard Hall, only recently remodeled as part of the library complex. Since there are no natural plantings in this area, there is a strong play between brick pavement and open sky. Noguchi's first understanding was that the architect wanted something to clarify this open space so he proposed a fountain; then, he followed through with the existing sculpture. Both proposals indicate that Noguchi did not see the new square as a sculpture court but rather as a unique and central garden.

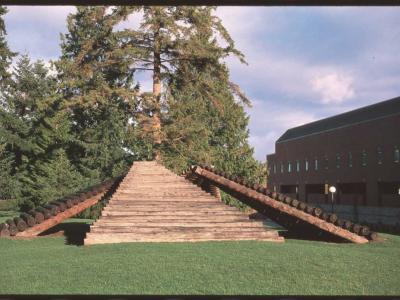

At the time of his commission Noguchi was traveling back and forth between his studios in New York and Japan, but he already was a seasoned world traveler. His two concepts for Red Square stem from his appreciation of both the ancient architecture and landscapes of the East and West. Among his inspirations were the pyramids of Egypt and the pyramids and cones of sand in Zen gardens; Greco-Roman architecture and an 18th-century Indian garden with astronomical instruments; the formal paving patterns of Italian piazzas, the interlocking square and circles of the Chinese Altar of Heaven, and the plowed fields of the great Midwest. Noguchi also had a strong desire to create playgrounds for children so he looked at abstract shapes from these ancient cultures and nature. He saw these areas as places for leisure as well as for daily recreational and experimental education. But Noguchi's spatial concepts were not just tied to examples of architecture and landscape. In traditional Japanese poetry and painting, there was a celebration of seasons: moon viewing, snow viewing, blossom viewing. His interest in time extended from traditional Noh theater with its poetic dislocations of events to Buckminster Fuller’s futuristic technology. The meanings of altered spaces could come from bending down to enter the curved doorway of a rectangular Japanese teahouse as well as bending down to lift a dancer into the air.

Initially, Noguchi proposed for Red Square ''a fountain resembling a field blanketed with daisies in profuse bloom." Whether daisies or lotus petals, Noguchi's nozzles would extend out into the circular pool to create a pattern of radiant energy. This water pattern would draw the eyes of the students up toward the heavens but the design became too expensive to pursue. Earlier in his career, Noguchi had made the statement that ''seeing stars from the bottom of a well can also be a sculpture, '' so in this case, he changed his proposal to a cube with open spaces through which one could see the sky. Yet in both singular designs, Noguchi intended his work to integrate the plaza into a single sculptural space similar to a playground, or even a world stage.

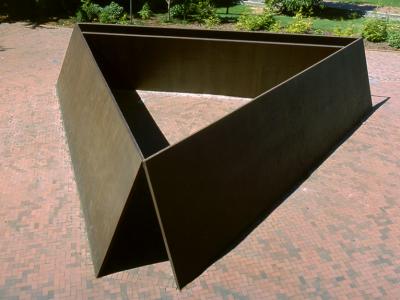

Skyviewing Sculpture pulls together many of the elements seen in some of Noguchi's earlier works. First, some of his early proposals (Play Mountain and Monument to the Plow, both 1933) incorporated a three- or four-sided pyramid, a key shape relating to the ancient earth. Western's sculpture is a ''cubic pyramid." Secondly, by creating set designs for the Martha Graham Dance Company, he began to understand how to inter- weave the abstract void of the stage to his forms and the performers. A description of the design he executed for Graham's Frontier (1935) is strikingly similar to Skyviewing Sculpture; both imply a penetration of space. ''A rope, running from the two top corners of the proscenium to the floor [of the] rear center of the stage, bisected the three dimension al void of stage space. This seemed to throw the entire volume of air straight over the heads of the audience." The dancer would start from and return to the section of a log fence at the rear of the stage. In Red Square, the ''frontier'' begins at the spectator's feet where the cylindrical bases send forth radiating lines on the brick pavement as well as lifting the viewer and the sculpture into the sky. Thirdly, Noguchi had created a sunken garden (Beinecke Library, Yale University, 1960-64) where all three shapes in the one Skyviewing Sculpture pyramid, circle, and cube are found on a marble pavement with radiating lines. At Yale, Noguchi worked out a total concept using long- held symbols: (a) the square, an earthly place of humans; (b) the pyramid, the ancient geometry of the earth; (c) the circle, the ring of energy as well as the zero of nothingness; in Japan, the sun and its attribute, the mirror; (d) the cube balanced on its point as chance, the man-made imitation of nature.

Skyviewing Sculpture is part of a tipped cube series that began with the solid stone in the Beinecke Library's sunken garden. Four years later, for a corporation in New York City, Noguchi made Red Cube of steel plates with a hole in the center. While the solid cube in Yale's sunken garden represented nature and past human history, the metal cube in New York brought man's technology to the foreground. While the hole could have negative connotations of ''an abyss," Noguchi used the positive nature of the void - the opposing energy or duality implied in the human condition in relation to both nature and technology. Most importantly, as a tipped cube, Western's sculpture rests on three points, suggesting the University's square as a monumental base for man's aspirations, including technology.

While some roll their eyes when students describe the sculpture like the helmeted face of Darth Vader, Noguchi went on to create a hydrodynamic, pyramidal fountain in Palm Beach (1974) with clearer suggestions of a science-fiction spacecraft; earlier this shape was also one used for a design for a playground. But also in Yale's sunken garden was the white circle or sun, from which he developed Black Sun (1969) for the Seattle Art Museum in Volunteer Park; Black Sun was made at the same time as Skyviewing Sculpture. If as Noguchi stated, ''The white sun belongs to the East where the sun rises, the black sun in the West where the sun sets," one wonders if Western's sculpture - a cubic pyramid with circles - does not belong to this East-West group. In fact, this cubic pyramid with circles onto the sky is one of his most total cosmic concepts.