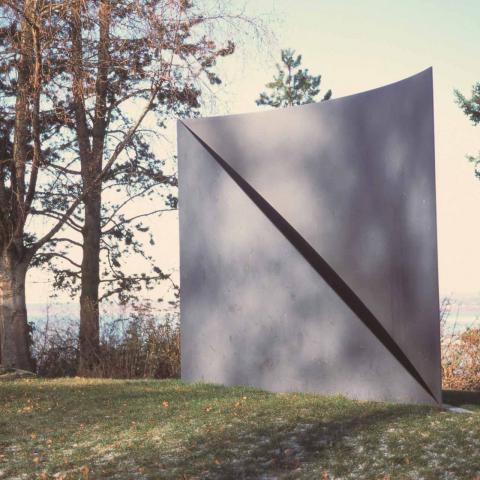

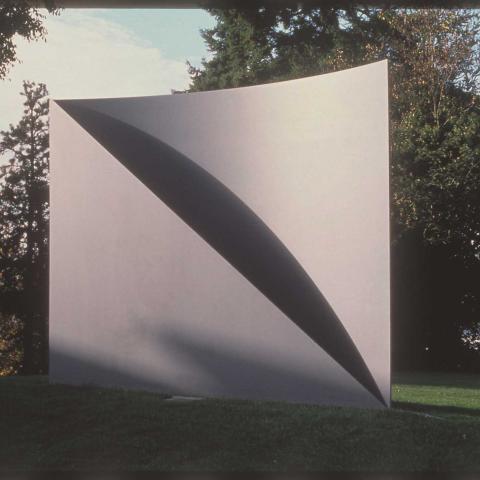

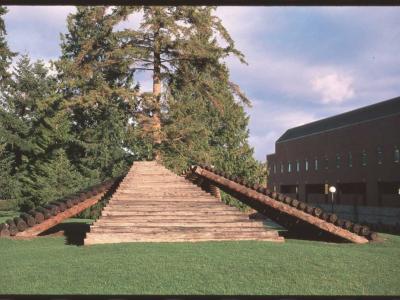

Robert Maki, Curve/Diagonal, 1969-70

Robert Maki, 1976-79.

Painted corten steel. 8' h. x 10 1/2' w.

Photo credit: Matthew Anderson

Gift from the Virginia Wright Fund, 1980; installed 1981.

Description

Although actually constructed in 1979 for a gallery exhibition, Maki's sculpture comes from a series of studies done between 1974 and 1976. Its siting at Western was crucial because he was interested in the direction of the sun assisting in the restructuring of the work. Depending on the time of day, weather conditions, and positions of the viewer, the shape and dimension of the real curve will change. Similar to Judd, Maki is interested primarily in perceptual issues rather than metaphoric references.

By framing the student in his photograph, Judd had exceeded the role of mere architect and encouraged a role for the viewer. Maki, a graduate of Western (1962), took up this perceptual theme in his own sculpture, but has pushed the ''envelope'' in his quest to understand how we see. Earlier as a Western student of industrial design, engineering, and drafting, Maki brought to his art a concentrated focus on geometry's elements of line and plane.'' Similar to Caro's India, Maki's Curve/Diagonal (1976-79) was purchased during a gallery exhibition, so that the work had to undergo his critical study of the difficult transition from studio or gallery to public place. Along with defused memories, the integration of landscape with dominant buildings came into play in Maki's decision to site Curve/Diagonal along High Street. Now the new dorms of Mathes and Nash next to the student commons faced both the Greek revival Edens Hall and Paul Thiry's early modern, stacked concrete apartments in Higginson Hall on the other side of the street.

Full text

From 1968 to 1969, during a NEA fellowship, Maki had made studies through both drawings and geometric cut-outs in order to visualize the numerous ways an object can be seen. While he could skillfully draft triangles with wavy or rounded diagonals in varying views with different ground lines and elevations, he took his triangular cutouts, joined by a fold, outside to stand upright in the natural sunlight. Here, light was the actual agent for drawing out or reversing the stability of their shapes. In these earlier studies, Maki made a pre-proposal for his alma mater in which one triangular cutout would be set on a hill, perhaps Sehome Hill or the west face of the ledge on which the University sits. The work would be situated so that the hill and changing light would seem to leach into the shape, perhaps even evaporating some of its hard edges. One drawing in particular accented details of just one plane of this cut-out with rounded diagonals; one rounded edge emerged from the ground line as if a rock or mountain.'"

Twelve years later when Maki had the opportunity to site a work at Western, he no doubt remembered his earlier drawings. However, not only had the campus changed with new buildings and more artworks since he was a student, but also he came with a more complicated, fabricated work. On the west side of campus, two new dormitories (Mathes and Nash Halls) had been built on the outer edge or ledge of campus. While some in the community might have criticized their looming presence on the Garden Street Hill, others marveled at their curving facades reminiscent of the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto. Coincidentally, the younger Finnish-American artist finally chose to site his work adjacent to Mathes Hall across from Edens Hall where he had been as a student. As a student on the porch of Edens Hall, he could see beyond the hill on which the University rested, but the forested Sehome Hill to his back gave protection. In the distance was the bay; in the rear was the felt but unseen presence of Mt. Baker. However, in the defining moment of these memories he allowed two details to emerge. First, he placed his own clear structure made out of an industrial material beside a rock, the tip of a larger geological formation that runs under the ground and erupts with an irregular line at the point of his sculpture. Secondly, he turned the outer curved back of his sculpture so it would echo the larger curving facade of Mathes Hall. Attached to the sculpture's curved back are two triangular flaps that fold across its interior. While the overall shape does not disappear into the landscape or hill, varying light conditions at different times of the day and seasons either flatten or open up this hidden structure, an envelope-like shape. As opposed to the function of the dormitory, Maki's construction only contains perceptual issues. And unlike the expansive dormitory, Maki's sculpture has a different sheltering capacity.

© Sarah Clark-Langager