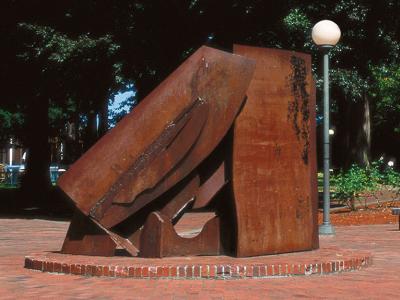

Alice Aycock, The Islands of the Rose Apple Tree Surrounded by the Oceans of the World for You, Oh My Darling, 1987

Video

Audio Description

Alice Aycock, 1987.

Waterfilled cast concrete. 9' h. x radius 10.5'.

1987 Sculpture Symposium funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, Washington State Arts Commission and private donations.

Description

Rather than forcing the viewer to traverse the structure, as in Serra's sculpture, Alice Aycock emphasized a bird's eye view. Inspired by tantric drawings of the origin of the world, landscapes and various views of heaven and hell, she focused on the sacred mountain Meru which is at the center of the universe and which has many different plateaus and islands. She transformed a 2d metaphor into a 3d theatrical structure. The fountain with its flowing water sets up a dialogue between the natural and the artificial or fantastic world.

Both Pepper and Aycock are interested in archeology where nature and architecture mingle. Both make reference to Etruscan tombs. Pepper concentrates on the tomb's contents: how the slag of that culture's remnants can become a new material for tools. Decades later, she makes a vertical sculpture. Aycock notices how the Etruscans carved tombs, a type of architecture, out of the earth. She creates a work close to the ground, such as Islands of the Rose Apple Tree Surrounded by the Oceans of the World, For You, Oh My Darling (1987).

Full text

An avid reader of literature, history, and architectural books, Aycock finds that architectural language more than often speaks only of function. But she feels it can exemplify more soaring emotions and ambitions, as did the great monuments of the past and present civilizations: Mycenaean beehive tombs, pyramids, medieval churches, Renaissance temples, even today's roller coasters. In creating her own structures she wants to investigate these spiritual origins in order to capture her memories and fantasies. One of her methods is to use architectural structure as if it were script. In the late eighties she became intrigued with primary methods of forming letters or figures: Egyptian hieroglyphics, the Rosetta stone, which combined Greek inscriptions and Egyptian picture-writing, and Tantric diagrams. For example, she gave herself the problem of drawing the two-dimensional symbols on the Rosetta stone as if they were not cut in relief but actually in three dimensions. She went further by transforming these symbols into imagined rooms or buildings as if she had drawn an isometric view of a modern city. She was interested in archeology's ''memory palaces'' or how ancient civilizations had built a warren of rooms where each held a certain key figure or idea. In another drawing she explored how the Indian World View (1985) could be a mental construction or map of the entire world.

In Aycock's sculpture for Western she has cast her script in concrete; the low edifice is a fountain with a narrative about a place, a world, and a person. Whereas FitzGerald's fountain symbolizes the sounds and vertical cycles of Washington's forests, Aycock's fountain gives life to the surface and just under the earth. She was stimulated by Tantric drawings that place the symbolical Mount Meru at the cardinal center. The mountain is also an outward representation of the center of the inner body; within the center is a spinal tube called the merudana. From the center, plateaus and regions radiate out from continents to constellations. Beyond the farthest visible circle lies the sphere of the invisible. Aycock's Mt. Meru is a circular depression reaching into the concrete or earth and a mountain or body that rises when filled with water. She selected just two of the regions that circle Mt . Meru. This island with apple trees surrounded by the oceans is not unlike the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts of the United States or even regions of Washington State. Beyond the persistent memories of births and deaths in her own family, this fluid or water slowly circles and pushes against the outer concrete wall to send ripples into an unknown life or place. Here, the natural colors of rain and mildew sink into the concrete. Aycock's work is mesmerizing in the sense that she places the viewer between two worlds. When she created the fountain during the summer symposium of 1987, she sited it adjacent to Carver Gym and a parking lot in a low-lying area. As the viewer emerged from the tree-lined parking lot he could veer from the main side walk into a glade containing her water-filled, cast concrete structure. In this low ground literally below the high grade of the major north-south campus walk, her circular form with extended arms beckoned the viewer into its center. Walking between the extended concrete arms with water channels, the viewer comes to gaze into the circles imprinted with a maze of shapes. The natural element of water fills or completes the artistic water imagery: passages, channels, moats; abstract wavy lines and boat cut-outs; the linear structure of docks or moorage. At that time, the more prominent view of Aycock's work could be seen from the walkway between Noguchi's observatory to the north and Holt's observatory to the south. As the viewer traversed this higher path, he could sidestep into a resting or viewing station that looked down onto her work. From this bird's-eye view, Aycock's fountain has more cosmic allusions to the orb of the earth, oceanic worlds, and gardens of paradise.

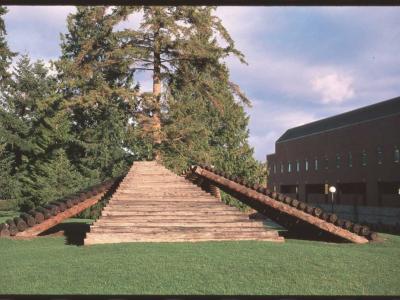

Rather than a simple bird, some of Aycock's favorite images of flight imply a more elaborate narrative: images of angels in Italian paintings; a photograph of a man leaping from one rock to the next; a woman on a horse jumping from a scaffold; the Wright brothers in a glider. In her original creation and siting she wanted a bird's-eye view because she equated flight with a state of desire. When the Chemistry building and its accompanying science, math, and technology lecture hall were constructed in the mid and late nineties, Aycock's fountain was threatened. But the architects' solutions were to curve the encroaching end wall of the Chemistry building and later, to add to a walkway between the two buildings a series of steps that cascade down to her work. She was pleased because another of her favorite cultural images is a stair well by Sangallo in Orvieto where ''steps wind down deep into the earth; two sets of staircases wrap around each other, one descending, one ascending and ledges where you stop; you feel as if you are suspended in air."

© Sarah Clark-Langager