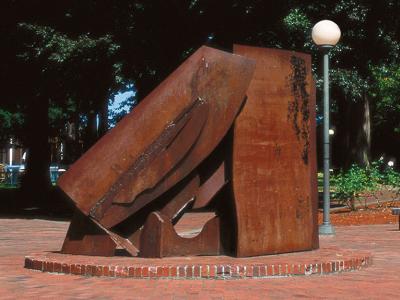

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Manus, 1994

Magdalena Abakanowicz, 1994.

Bronze with beeswax. 15' h.

Photo credit: Jesse Sturgis

Western Washington University in partnership with one-half of one percent for art law, Art in Public Places Program, Washington State Arts Commission.

Description

Walk along the sculpture with Google Street View

A deeply rooted respect for and close observation of nature have always been reflected in Magdalena Abakanowicz's preference for materials and themes. As part of the "Hand-like Trees" series begun in the nineties. Abakanowicz's sculpture "represents a metaphoric bridge between a form of nature and a human form." The artist chose the site at the south end of campus because she felt her work would link the natural beauty of the area, such as the trees of Sehome Hill, with the human activity of the campus.

Similar to di Suvero, Abakanowicz has utilized both the image and the metaphor of the hand to respond to cultural conditions. In her work for Western, the separate elements of tree trunks, human bodies, bark, skin, heads, and fingers come together in Manus (1994). To understand the origin of this work, it is important to first look at an earlier fiber sculpture, Hand (1976). Here, with its thumb tucked into the palm and likewise with the remaining fingers curled inward, this body part resembles the brain. While she can speak scientifically about the brain's divisions and its functions, she is more interested in connecting its structure to the art process. At times she acknowledges the conflict between these centers: physiological functions working with both instinctive and conscious behavior result in wisdom and madness, dream and reality. In other cases, she welcomes the intricacy of biological systems, including those of the body. Similar to a scientist, she involves herself in constant observation of natural phenomena.

Full text

For example, having grown up in the dark forests of Poland, she was eager to see the tropical rain forests of Papua New Guinea. Research followed by experimentation leads her to different techniques, materials, and avenues. In 1990, Abakanowicz proposed to the French government a new way to develop the landscape of the urban region La Defense. Based on her conception that the landscape was a body and that architecture was a living organism, she translated this area's traditional tree-lined gateway into twenty-five-story-tall ''arboreals." These man-made, tree-like towers covered with real vegetation would provide healthy, energy-efficient, economically productive residential and commercial spaces. While her Arboreal Architecture proposal was accepted for study, Abakanowicz's real questions were: What solutions can the human brain invent? How will the human species grow? What new ways of synthetic thinking can an artist provide? Out of this project Abakanowicz began to develop her Hand-like Tree series in 1992.

Interestingly, when Abakanowicz visited Western in 1993, she made two proposals. One dealt with the theme of biological growth and renewal metaphorically worked out by using sandstone boulders. While the architects were planning the Biology building and adjacent plaza, huge boulders were being piled high in the grassy area of the future Haskell Plaza. Attracted both by the source of the boulders dug from the devastated ridge and also by their shapes, she proposed a new cycle of her earlier ongoing work Embryology (1978). In stone rather than soft burlap, these sandstone rocks would be rescued boulders as well as elemental forms, oval shapes with varied connotations such as cocoons, nesting eggs, and brains. Her other proposal was a singular work from the Hand-like Tree series where a Styrofoam shape would be carved with a large kitchen knife, built up with plaster, and transformed into bronze at the Venturi Arte Foundry, Bologna. Although a very difficult decision, the committee finally accepted the latter proposal. While siting her sculpture alone near the trees of Sehome Arboretum and the tree-lined entrance of campus, Abakanowicz knew that her work was on the edge of further campus development southward. But unlike the ''arboreal," Manus merges the image of a massive amputated tree trunk with a giant defiant hand.

Abakanowicz is drawn to the image of the forest because it draws her back to her past. As a child in Poland she had played in the forest. Later in life, she would remember that the graves of World War II had replaced those green markers. But just as she does not give individual features or gender to her figures, she universalizes the condition of man at war and the devastation of the world's forests. Returning often to the forest as an artist, she noticed the spines of old tree trunks, the similarity between humans and trees with cut limbs, and young trees growing inside or on top of stumps. From one view, Manus is a tree with an open cavity as if blasted by nature and/or war. However sheltered deeper within this torn trunk are the veins of a leaf as well as those of an inner palm. From another view, Manus is planted firmly in the earth with its trunk rising to a clenched, knuckled hand. As if emerging from the mantle of the forest, the singular form evokes a human being dressed in a cloak waiting to help with the necessary reintegration of man and nature and man with man. Abakanowicz has the power to make an image that is situated in history as well as local in its evocation of the strength of nature in life and death.

© Sarah Clark-Langager