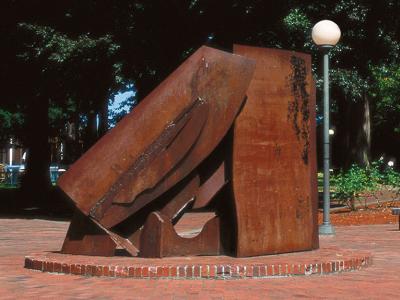

Donald Judd, Untitled, 1982

Donald Judd, 1982.

Corten steel. 7 1/3' h. x 7 1/3' w. x 14 2/3' d.

Photo credit: Rod del Pozo. © 2020 Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Gift from the Virginia Wright Fund.

Description

Donald Judd’s untitled sculpture has been a part of the sculpture collection at Western since 1982 but was removed from campus in 2014 due to serious corrosion. High water table and poor draining at the sculpture’s original site had resulted in long term exposure to moisture and standing water. A conservation plan was developed to save this important sculpture and restoration work started in the fall 2018, made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (MA-30-18-0412-18). The sculpture was returned to campus a year later and placed in a new, drier site by the University’s main entrance. The site matches the old site, being a minimally landscaped grass covered area, and was approved by the Judd Foundation. Back in public view, the sculpture is again available to students, educators and the community at large for enjoyment, research and interpretation.

The Institute of Museum and Library Services advances, supports, and empowers America’s museums, libraries, and related organizations through grant making, research, and policy development. The IMLS vision is a nation where museums and libraries work together to transform the lives of individuals and communities. To learn more, visit www.imls.gov and follow IMLS on facebook.com/USIMLS and twitter.com/us_imls

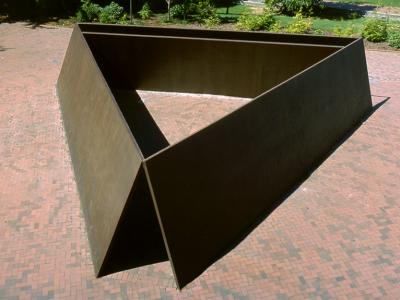

In his sculpture Judd has championed a maximum clarity in form and material. He has rejected metaphysical and metaphoric speculations and has tried to emphasize what art can express as true. To him, that truth was accumulated through concrete experiences and perceptual issues. With his ongoing series of boxes, he has established the versatility of such a simple shape. In his work for Western, the exterior sides, as expected, are perpendicular to the open ends; however, the interior panels are on the diagonal, thereby creating an unusual sense of space. He sited the work on the lawn so that his sculpture frames at one end Old Main on the lawn and in the distance the Canadian Coastal Range.

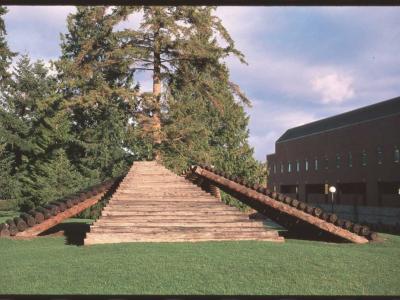

In the seventies, Judd had begun to think more about how his art had similar subject-object relations peculiar to architecture. Yet, if his ''specific object'' could be occupied, was it necessarily a building? By the time he moved from the streets of New York City to the plains of Texas in 1976, he had created a full range of work that had no other concept but the literal space within the hollow-like box itself. Any relation ship would have to incorporate ''virtually the whole room or area outdoors. "When he came to Western in 1981, he first proposed a series of architecturally sealed, concrete boxes set one after the other on a knoll parallel to the walkway adjacent to the field track in south campus. He finally decided on one large Cor-ten box with open ends and with interior planes set on the diagonal to the box's perpendicular sides. He cited his Untitled (1982) work on the lawn of Old Main.''

Full text

The fact that this new type of object was a hybrid - not painting, not traditional, solid sculpture, not functional architecture - does not contradict Judd's insistence on the independence of things. Conversely, he also sought a feeling of wholeness in his work. He felt that his procedure of making different hollow-like boxes provided a structuring experience for the viewer. His attention to a material structure would create the greatest intensity between the viewer and the immediate space of the specific object. His new architecturally scaled work could provide the core of a larger, complex underlying structure.

Inside Western's "box" there is an earlier method of using perspectival lines or planes to depict space. However, Judd was opposed to the western idea of fixing space, so he also opened up the ends of the boxes to allow occupancy and a greater "ambient situation." His concept of order countered hierarchical relationships, particularly those of European rationalism, because he was against any grand, immutable scheme or composition of knowledge that excluded information gathered by the senses. He believed that Cartesian rationalism failed to reflect the disparate conditions of the 20th century. He saw "an existential universe in which parallel lines meet, in which interior and exterior (subjectivity and objectivity) are co-extensive and finally interchangeable, in which order and disorder (symmetry and asymmetry) have equal value. . . ." Furthermore, as one critic has stated, he realized that ". . . all rationalism [is] the same, whether that of a higher, purer harmonic, or that of capital and labor."

Another artist, Robert Smithson, described Judd’s work as "uncanny,” a strange adjective for what was supposed to be rigorous, right-angled work. What Smithson meant was for all Judd's repetition of this defining box structure in various permutations and materials, Judd's space is "elusive" in what it captures, holds, or "misses." As Smithson said: "Time has many anthropomorphic representations, such as Father Time, but space has none. There is no Father Space or Mother Space. Space is nothing, yet we all have a vague faith in it." Suggesting an analogy between abstract space, mineral deposits, and Judd's boxes, Smithson still found Judd's space "elusive."

In retrospect, perhaps what Judd was thinking about was his situation in Marfa when he first proposed the concrete boxes one after the other for this campus. In Texas he was working out specific spaces for his artwork, where each object contains space and is contained in space; where windows and doors, rooms, courtyard, and sheds would frame the expanse of the fields, plains and mountains in the distance; where the concrete boxes in those outer fields would take this underlying unity one step further. However, Judd’s mental process also incorporated feeling and particular experience. That experience of the university was more like a series of smaller rooms--architecturally enclosed spaces--on a fortified hill that was part of a larger natural landscape. In the end, he placed his Cor-ten work besides the Greek columned porch of Edens Hall (a vintage 1919 women’s residence hall on first quad), which looks across the Canadian Coastal mountains. One open end of his work looks up the sloping lawn to Old Main, framed by the towering trees of Sehome Arboretum, and the other end measures the exact interval between the newer dormitories of Mathes and Nash Halls, which allows a distant view of these mountains. In a statement for a catalogue in 1993, Judd actually referred to his Untitled (1982) work at Western as a piece where "space in the work and outside the work is important." In general, he felt that the "vocabulary of space of the past should be reconsidered" because, as in Greek civilization, there was a wholeness in a relationship not just made up of parts of a box or room but rather consisting of art, architecture, and nature. But of equal importance to his text in this catalogue, Judd chose a photograph specifying the temporal dimension of his Untitled work, which supported the idea of the nondistinction between the perception of art and architecture. His view through the contained space captured both the traditional architecture of Old Main and a passing student.

© Sarah Clark-Langager